by Elyse Edwards, Graduate Student Intern (Simmons College GSLIS)

‘In times of great struggle and conflict in the South,’ Congressman [John] Lewis said, ‘during the freedom rides of 1961, when young people were being beaten by angry mobs in Montgomery and when fire hoses and dogs were being turned on people in Birmingham, people always said, Call Burke.’

[“Burke Marshall, a Key Strategist Of Civil Rights Policy, Dies at 80,” © The New York Times Company, June 3, 2003.]

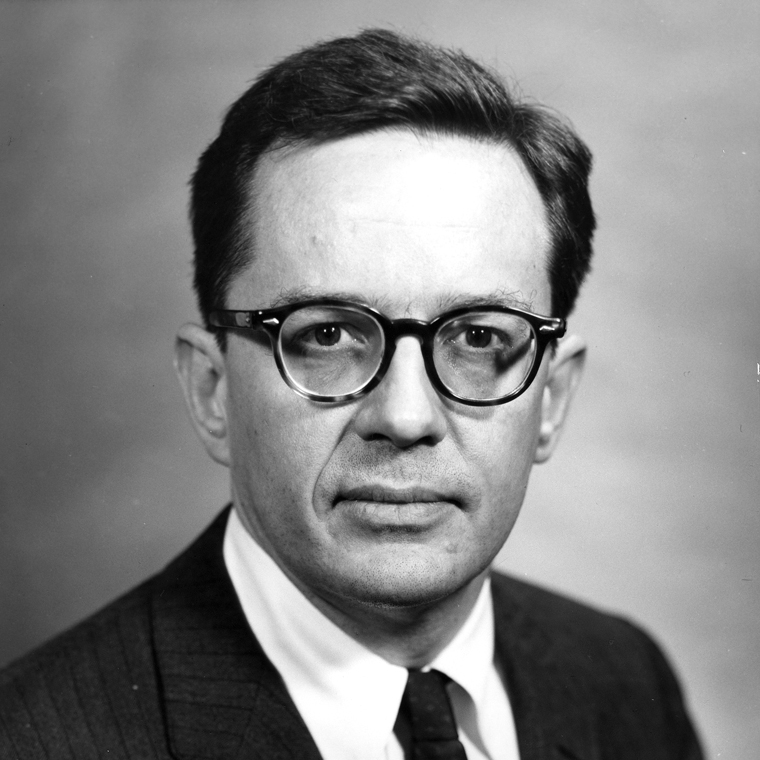

Civil rights-related materials from the Burke Marshall Personal Papers represent the latest addition to the digital archives of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. As Assistant Attorney General in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice (DOJ), Burke Marshall oversaw landmark moments in civil rights and was instrumental in developing the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The newly-digitized material focuses on civil rights issues such as: desegregation of interstate transportation and travel facilities; school desegregation (including James Meredith’s fight to enter the University of Mississippi); voting rights; and legislation.

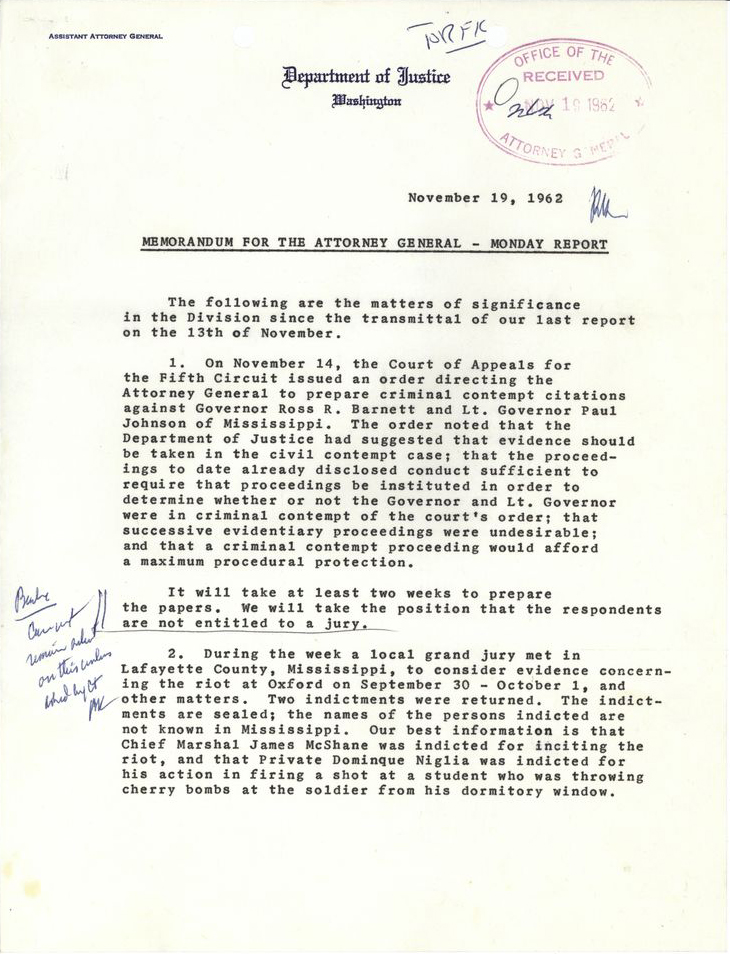

A memorandum from Burke Marshall to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy discussing pending civil rights cases, issues, incidents, and Department of Justice actions, 19 November 1962. View the entire folder here.

A memorandum from Burke Marshall to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy discussing pending civil rights cases, issues, incidents, and Department of Justice actions, 19 November 1962. View the entire folder here.

Burke Marshall was born on October 1, 1922, in Plainfield, New Jersey. He received his undergraduate degree from Yale University before serving as a Japanese translator and cryptanalyst in the United States Army during World War II. After the war, Marshall returned to Yale for his law degree before joining the law firm of Covington and Burling. In 1961, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy appointed Marshall to the post of Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, a position he held until 1965. Following his resignation from the Department of Justice, Marshall returned to Covington and Burling before joining I.B.M., where he served as Vice President and General Counsel. In 1970, Marshall accepted a position as Deputy Dean and Professor at Yale, where he taught classes on political and civil rights for over three decades, eventually earning the title of Professor Emeritus.

Note to file by Burke Marshall regarding demonstrations in Jackson, Mississippi, 29 March 1961. View the entire folder here.

Note to file by Burke Marshall regarding demonstrations in Jackson, Mississippi, 29 March 1961. View the entire folder here.

As head of the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, Marshall took immediate action to enforce desegregation in schools and in interstate travel. Never one to send representatives in his stead, he worked directly with affected communities and established relationships within them. In the summer of 1961 Marshall visited every city in the South with schools that were slated for desegregation that fall, speaking with state and local officials and community members to facilitate open dialogue. Marshall preferred to seek resolution through open discourse, a hallmark of his approach to easing racial tensions and encouraging voluntary integration.

A letter from James Meredith to the Justice Department requesting that the federal government step in to enforce integration in public education and protect the rights of all citizens, 7 February 1961. View the entire folder here.

A letter from James Meredith to the Justice Department requesting that the federal government step in to enforce integration in public education and protect the rights of all citizens, 7 February 1961. View the entire folder here.

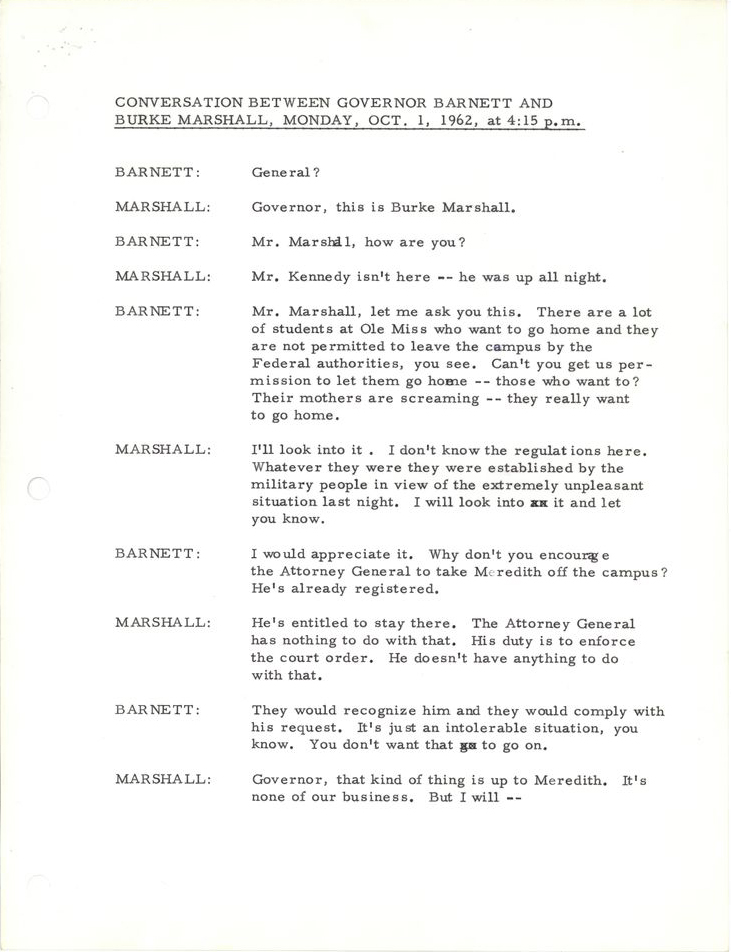

One of the major challenges that Marshall faced was the integration of the University of Mississippi. Marshall spent weeks traveling between Mississippi and Washington, D.C., working with state and local officials to ensure that James Meredith would be admitted peacefully to the school. Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett opposed Meredith’s admission, citing state laws. Despite numerous telephone calls with Marshall and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Governor Barnett refused to uphold the Supreme Court ruling banning segregation in public schools. United States Marshals were sent to the University of Mississippi to maintain peace while the ruling was enforced, leading to a violent confrontation between students and those opposed to the admission of Meredith. Careful preparation and close vigilance by Marshall and the Attorney General, as well as protective details provided by the U.S. Marshals, ensured Meredith’s successful enrollment in the University of Mississippi on October 1, 1962.

Listen to some of the telephone conversations among the President, Attorney General, Governor Barnett, and Burke Marshall here and here.

Transcript of a telephone conversation between Burke Marshall and Governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, regarding the admission of James Meredith to the University of Mississippi, 1 October 1962. View the entire folder, containing additional transcripts of conversations among the Governor, President Kennedy, and the Attorney General, here.

Transcript of a telephone conversation between Burke Marshall and Governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, regarding the admission of James Meredith to the University of Mississippi, 1 October 1962. View the entire folder, containing additional transcripts of conversations among the Governor, President Kennedy, and the Attorney General, here.

Burke Marshall visited the southern states regularly, holding numerous meetings with various leaders including Governor Barnett, Governor George Wallace of Alabama, as well as mayors, businessmen, and lawyers, to discuss potential solutions for easing racial tensions. The success of civil rights legislation and its implementation was influenced by the tenacious efforts of Marshall and his staff to open up channels of communication and to mediate sharp disagreements within communities. Additionally, Marshall used legal recourse when necessary to enforce civil rights legislation; he and his staff actively applied the rule of law to civil rights cases, a key strategy for enforcing voting rights.

Memorandum from Burke Marshall to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy regarding a letter from NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers about voting rights infringement cases in the South, 15 March 1961. View the entire folder here.

Memorandum from Burke Marshall to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy regarding a letter from NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers about voting rights infringement cases in the South, 15 March 1961. View the entire folder here.

Letter from Burke Marshall to Laura McCray, who was appointed a voting referee in Alabama to ensure fair and lawful registration for all voters, 10 May 1961. View the entire folder here.

Letter from Burke Marshall to Laura McCray, who was appointed a voting referee in Alabama to ensure fair and lawful registration for all voters, 10 May 1961. View the entire folder here.

At that time, voting restrictions served as a major vehicle of oppression in the South. Literacy tests, poll taxes, and intimidation were mechanisms of discrimination used against African Americans, leaving them unable to exercise their right to vote. The resulting disenfranchisement meant that African Americans were unable to exert any political influence where they lived. To address this problem, Marshall and his team undertook a massive legal effort to guarantee voting rights. To that end, inspections of voting facilities, voting records, and test administrators were conducted in nearly 200 counties to ensure that voting regulations were administered fairly.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, originally proposed by President John F. Kennedy in 1963, was the culmination of years of hard work undertaken by Burke Marshall, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, and countless others working for, with, and alongside the Department of Justice. Previous civil rights legislation, including the acts of 1957 and 1960, lacked adequate enforcement provisions and their defense relied heavily on the 14th Amendment. Marshall approached civil rights legislation from a different angle, invoking the federal government’s constitutional power to regulate interstate commerce.

As racial tensions grew, the necessity for legislation to protect civil rights activists and civilians and to permit federal intervention became apparent. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a source of heated debate, as many viewed it as a violation of states’ rights. Regardless, it was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on July 2, 1964 and was a crowning achievement for those committed to expanding and ensuring equal rights for all Americans. (You can read more about the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on our blog and on Tumblr.)

Burke Marshall’s contribution to the field of civil rights is enduring and his role as a consummate public servant was well-recognized. On Marshall’s letter of resignation as Assistant Attorney General, President Lyndon B. Johnson noted, “I have never known any person who rendered a better quality of public service.”