by Stephen Plotkin, Reference Archivist

The death of Donald M. Wilson in November 2011 represents the most recent loss of a notable Kennedy Administration official. In addition to being a high-ranking member of the Kennedy Administration, Wilson was the last living member of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM), the advisory group that President Kennedy established to help guide him during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

A career journalist who spent most of his working years with Time-LIFE Inc., Mr. Wilson took a leave of absence from that company in 1960 to work for President Kennedy’s campaign. After his election, the President made Mr. Wilson Deputy Director of the United States Information Agency (USIA) under Edward R. Murrow. In that capacity, Wilson exercised considerable responsibility as Murrow’s ability to fulfill his duties was hampered by illness. It was in Murrow’s stead that Wilson attended meetings of the EXCOMM.

For a group that literally held the fate of the world in its hands, the EXCOMM is relatively obscure today. Its history, though, is a fascinating one.

At the end of World War II, the United States, which had been isolationist in the pre-War years, found itself at the center of world affairs. It was clear the country would need a mechanism for evaluating and managing the many issues and concerns that came with this new role. Precedents were available from the war effort. Cooperation with the British had familiarized U.S. officials with their use of committees and committee organizations to handle the coordination of government policy. In particular, U.S. officials had studied the British Committee of Imperial Defense, a body created in 1904 to coordinate national security matters at the highest levels of government.

The first U.S. attempt to adapt this technique was the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee (SWNCC), which was established in 1944 to manage communications between the State Department and the military. With the signing by President Truman of the watershed National Security Act of 1947, which, among other things, created the Central Intelligence Agency and the Air Force as a separate wing of the military, the SWNCC became the State-Army-Navy-Air Force Coordinating Committee (SANACC). Although the committee continued in this new form, much of its function was taken over by another creation of the Act, the National Security Council (NSC).

The stated purpose of the NSC was to “advise the President with respect to the integration of domestic, foreign, and military policies relating to the national security so as to enable the military services and the other departments and agencies of the Government to cooperate more effectively in matters involving the national security.” As it first took shape, the Council was to comprise the President, the Secretaries of State, Defense (newly created by the Act), Army, Navy, and Air Force, and the Chair of the National Security Resources Board. The President was given latitude to bring in other executive-level officials as members. He was to preside over meetings or, if absent, designate another member to do so. Finally, the Act allowed for a career staff, headed by a civilian Executive Secretary, to provide support for the work of the Council.

It is interesting to trace the various structures, organizations, and re-organizations that the NSC underwent during the next decade and a half. As the creator and first adopter of the NSC, Truman in particular made numerous adjustments. Initially, he attended relatively few meetings, reasoning that in his absence discussions would be freer. After some legislative changes to the NSC in 1949, and with the beginning of the Korean War in 1950, Truman presided at almost all NSC meetings, which became much more frequent.

Upon arriving in the White House, Eisenhower ordered a top to bottom review of the NSC and its support staff. The resulting report by the President’s close advisor, Robert Cutler, made a number of major recommendations for change, although much of the system remained intact. One change was the creation of the position of National Security Advisor, which Cutler filled. With all the recommended changes in place by spring of 1953, there were essentially no significant modifications to the system for the next eight years, apart from the creation of the Operations Coordinating Board (OCB) later the same year. The Board was developed to fill a perceived gap in the oversight of the implementation of policy.

During the Eisenhower Administration, National Security Council meetings were held weekly at a set time (Thursdays, mid-morning), and the President almost always presided. Eisenhower was a vigorous and leading participant in Council meetings and was skillful at managing the NSC and in creating national security policy.

By the end of the 1950s, discontent with the NSC began to develop. The most prominent critic was Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, a Democrat, though criticism was also bipartisan. In 1959 Jackson persuaded the Senate to establish a Subcommittee on National Policy Machinery charged with studying, in a nonpartisan manner, the procedures of foreign and defense policymaking. President Eisenhower and his advisers opposed this effort and were reasonably successful in reducing the purview of the Subcommittee. Nonetheless, the Subcommittee’s report, released in the fall of 1960, was strongly critical, disparaging the bureaucratic, institutionalized manner of the NSC’s functioning and especially attacking the proliferation of committees and subcommittees within the Council and its staff.

In its report, the Subcommittee pushed for individual responsibility and more direct connections. As a Senator, John F. Kennedy had been a supporter of Jackson’s critique, and as President-elect he found the Subcommittee’s recommendations congenial to his style; Kennedy was apt to seek information and advice from particular individuals whom he thought might have something to contribute. Within the NSC, important changes facilitated this approach. Kennedy’s National Security Advisor, McGeorge Bundy, took over the functions of several former Eisenhower assistants, including many responsibilities held by the Executive Secretary of the NSC; Bundy in turn shaped the character of the NSC staff. Furthermore, NSC members had traditionally served the presidency through the structure of the Council. During the Kennedy Administration, that changed. The connection of the staff to the President became stronger and more direct; the Council also began to meet less frequently.

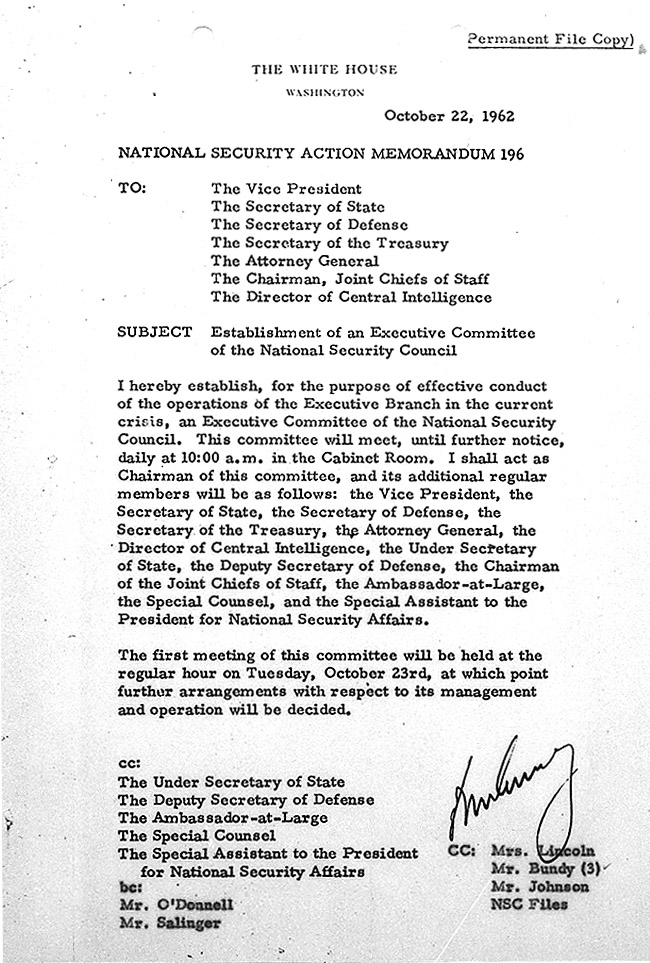

National Security Action Memorandum 196, which defined and established the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM).

It was within this environment that the group eventually known as the EXCOMM began to meet. The meetings began almost immediately following the discovery of missiles in Cuba in October 1962. However, textual records of those meetings do not exist until the official establishment of the EXCOMM on October 22, 1962–a week after the Cuban Missile Crisis began. Recorded conversations during the first week of the crisis (two days, October 16 and 18) may be found within the Presidential Recordings series of the President’s Office Files.

The EXCOMM was established by National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 196 and originally had twelve members: Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Secretary of the Treasury Douglas Dillon, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Director of Central Intelligence John McCone, the Under Secretary of State George Ball, Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric, Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Lyman Lemnitzer, Ambassador-at-Large Llewellyn Thompson, Special Counsel to the President Theodore Sorensen, and the National Security Assistant. Eventually, another fifty-nine individuals were cleared (over time) to attend EXCOMM meetings.

JFKNSF-339-006-p0001. National Security Action Memorandum 196, which defined and established the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, 22 October 1962.

Donald Wilson became a valued member of Kennedy’s EXCOMM (Bundy had particular praise for the work of the USIA), participating in one of the most delicate and dangerous situations ever confronted by a U.S. President. After President Kennedy’s death, Wilson continued with President Johnson for two years before returning to Time-LIFE, where he worked until his retirement in 1989. In his last years, Wilson was associated with the Independent Journalism Foundation. He published his autobiography, The First 78 Years, in 2004, and an oral history with him is available here at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

This post was based wholly on the following sources:

Organizational History of the National Security Council: Study Submitted to the Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate, by its Subcommittee on National Policy Machinery. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1960.

Organizational History of the National Security Council during the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations. Bromley K. Smith. Washington, DC: National Security Council, 1988.

Keepers of the Keys : A History of the National Security Council. John Prados. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1991.

Compilation of the National Security Act of 1947. http://intelligence.senate.gov/nsaact1947.pdf. Page published by the United States Select Committee on Intelligence Website (http://intelligence.senate.gov/index.html), 2006. Last consulted 23 December 2011.

“National Security Action Memorandum 196.” Papers of John F. Kennedy. Presidential Papers. National Security Files. Meetings and Memoranda Series. Box 339. Folder: “NSAM 196”. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.

Donald M. Wilson obituary. http://www.rfkcenter.org/node/206332. Page published by the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights (http://www.rfkcenter.org/home), 2011. Last consulted 23 December 2011.